As Libya descends into a bloody civil war, thousands of refugees are trapped in the crossfire. Some are forced to fight as mercenaries, while others are systematically raped, tortured or sold as slaves. One Italian is helping them tell their stories.

Not far from the Libyan border, in the yard of a house on the southern coast of Tunisia, Michelangelo Severgnini, an Italian man, bends over his smartphone and listens to the words of a man from South Sudan.

The man on the phone is more than 200 kilometers away, in a Libyan refugee camp near Tripoli. In a whisper, he talks about his deployment at the front — how he had to mop the blood of fallen soldiers off flatbeds, clean their rifles and stack them onto trucks. “Libya is not my country,” he said. “I had to leave my homeland because of another war. I don't want to fight, but the militias force me.”

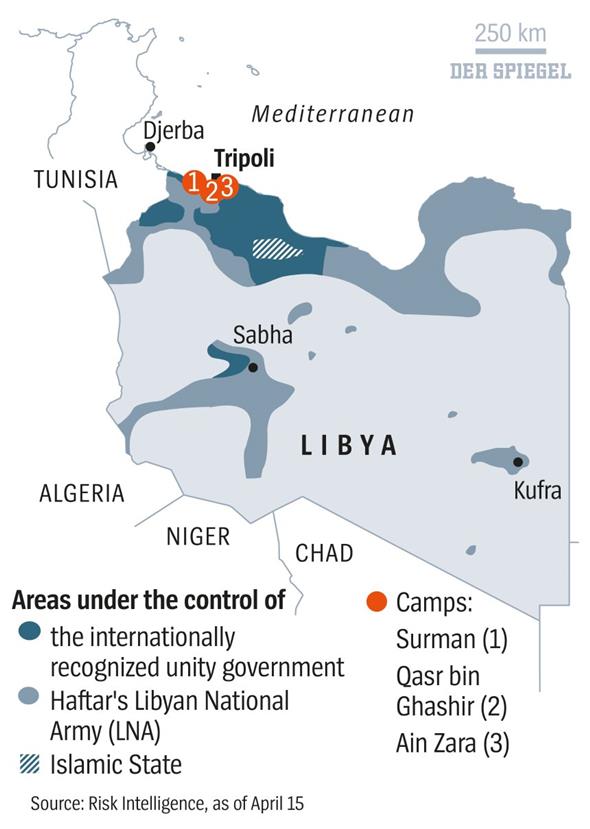

Libya was already a hell for migrants before the renewed outbreak of civil war. Thousands of people from African countries were thrown into Libyan prisons while trying to flee to Europe. Many have been tortured and sold as slaves. Now they are trapped between two warring sides: the unity government of Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj and the warlord Khalifa Haftar, whose Libyan National Army (LNA) controls the east of the country.

Since Haftar stormed the capital, Tripoli, in early April, the LNA and the militias loyal to al-Sarraj have been waging positional warfare. So far, around 300 people have died in the fighting and more than 42,000 have been driven from their homes. Haftar has been launching air raids against Tripoli since the beginning of the offensive. Human rights organizations accuse the unity government of forcing refugees to fight as soldiers, which if true would constitute a war crime. The government denies the allegations.

In the Qasr bin Ghashir detention center south of Tripoli, 890 men, women and children were surrounded and fired upon indiscriminately last month, presumably by Haftar's militias. Several inmates told Severgnini about the violence, sending him videos of blood-drenched people in which shots could be heard in the background. Amnesty International and Doctors Without Borders also filed their own reports. The reasons for the attack are unclear, as are the identities of the perpetrators. It's possible that the violence was intended as retaliation against migrants who fought for the unity government.

“We're like hard cash for the Libyans,” another South Sudanese man told Severgnini by phone. “We work for nothing, fight for nothing. We die before their eyes, in their war.”

Giving Refugees a Voice

The European Union has outsourced refugee deterrence to countries like Libya, but EU funds are siphoned off by the militias, and the conditions for refugees in the civil war-plagued country continue to erode. In the roughly 25 official refugee camps, people are often left to fend on their own, starving and without medical attention. The conditions are even worse in the unofficial camps along the smuggler routes run by the militias. According to human-rights activists, abuse, torture and killings occur there on a regular basis. The German Foreign Ministry has compared them to concentration camps.

Severgnini, 44, gives the refugees in Libya a voice. He uses WhatsApp to locate and contact them and, by doing so, creates a record of human rights abuses. “Tell me your stories,” he writes his contacts, “send them to me via WhatsApp. I need proof, so that people will finally believe us.” Severgnini uses the footage to curate a video blog, which he has titled “Exodus,” like the flight from Egypt in the Old Testament.

Severgnini is driven by his conscience. His country has closed its ports to refugees, conducts oil business in Libya and voted racists into the government. Severgnini said he wanted to expose the “obscene side of European refugee policy.” He's in contact with 400 refugees and has collected detailed stories from 100. Severgnini has also become the main person informing the United Nations about the conditions in the camps, the evictions and hunger strikes, the smugglers and the hidden tracts in prisons.

Notifications are constantly popping up on Severgnini's smartphone. He receives text messages, audio files and videos. Men and women send him reports from the camps as they hide under blankets or in toilets. They send videos of men squirming on the ground because their tormentors are dripping molten metal onto their backs. One of the torturers holds a gun to the men's heads while another films the scene with a smartphone camera. They use the victims' suffering to blackmail their families back home. The ransom is paid to a messenger. It's not unusual for the families to have to sell their land or take out loans to ensure their relatives' survival.

The refugees report to Severgnini about mass graves and how they were chained and forced to work after arriving in Libya. They toil as domestic servants, maids and as workers in fields, factories or on building sites. But they seldom receive any wages.

The worst atrocities usually happen to the refugees in the best shape. Soon after crossing the desert, they are sold at slave markets and so-called “Connection Houses” in southern Libya. Male victims are mostly forced to work, while the women are forced into prostitution. “It's like in the Middle Ages,” Severgnini said.

Refugees who have enough money with them are crammed onto rubber dinghies by smugglers and sent toward Europe. Nearly every week, people die crossing the Mediterranean. Others are intercepted, with the support of the EU, by the Libyan coast guard, arrested and sent to a camp.

No Safe Space

One 24-year-old Nigerian woman named Success Omoisiefe escaped the hell in Libya three years ago. She has since found refuge in a women's shelter run by the Catholic charity organization Caritas in northern Italy, though her memories of the horrors she encountered along the way continue to torment her. A DER SPIEGEL team met Omoisiefe for the first time at a camp in Libya in August 2016. Her photo was transmitted around the world at the time — now she wants to tell her whole story. She wants the world to know more about the camps in Libya.

Omoisiefe fled from a violent uncle in Benin City. Like most migrant women, she at first wasn't required to pay anything for the trip. Smugglers drove her and other women through the desert in an all-terrain vehicle, then locked her in a house in Libya in order to sell her as a prostitute later. After three days in captivity, Omoisiefe managed to escape with a friend.

The two women then came across a dirty house in which five Arabic-speaking men were loitering. Full of hope, they asked the men for help in English. That is when her ordeal truly began.

“They raped me anally,” Omoisiefe said. “They raped me orally. They spit on me. When they had had enough, they slammed my head against the wall.” She can't remember how long she was locked up inside the house, whether it was days or weeks. The men cut off her hair and masturbated on her face. “It was their game,” said Omoisiefe. “There was nothing we could do. It was their country.”

Three years later, Omoisiefe's body still hurts from the crimes that were committed against her. She reveals a dent on the top of her head caused by the butt of a pistol.

When the men lost interest in their sadistic game, they brought the two women to Camp Surman on the coast. DER SPIEGEL was allowed to visit the women's wing in 2016 for about 20 minutes and only while being closely watched. The camp was likely run by a militia that was cooperating with the government of Prime Minister al-Sarraj. Omoisiefe said she got the impression the five men had sold her to the guards.

Unthinkable Brutality

Omoisiefe was a prisoner in the camp for about two months. She shared a mattress with three other women, rarely received food and had to drink salt water. Omoisiefe witnessed a woman give birth and then cut the umbilical cord with a bottle that had been used as a urine container. The baby died. At night, some of the women were taken as sex slaves for guards and higher-ups.

“The guards left dead women in our cell for three or four days until their bodies were swollen,” Omoisiefe said. “They beat us when we spoke. I had no idea what would happen to me. I wasn't prepared.” One sentence she kept repeating, a mantra of sorts: “It wasn't easy.”

The women had to buy their way out of the camps. Anyone who didn't have relatives who could be blackmailed over the phone had the option of working in a brothel. Omoisiefe refused. Sometimes the guards would force the women to work. “They blindfolded us and brought us to rich Libyans, and we had to clean their homes,” Omoisiefe said.

Work assignments like this are often the prisoners' only chance of getting an idea of where they are and eventually freeing themselves. Omoisiefe met the Arab man whose house she was cleaning and he promised to help her. One night he released her and five other women from the camp and drove them to the part of the coast where the boats are launched. Rescuers intercepted Omoisiefe near the Italian coast. Aid workers then took her to Caritas in Ferrara.

Another reason Omoisiefe wanted to tell her story to DER SPIEGEL was because the plight of refugees in Libya has only gotten worse since her ordeal in 2016. Italy has closed its borders under the far-right populist Interior Minister Matteo Salvini. The EU, meanwhile, has stopped its sea rescue program in the Mediterranean. Civilians who take initiative privately have been intimidated. Together, these developments have only resulted in more people drowning in the Mediterranean or getting stuck in Libya.

'I Have Seen Things'

Those who are able try to make their way to Tunisia or Algeria. Take Samuel A., 22, for instance. A refugee from Eritrea, he has been on the move for five years — three of which he spent in camps in Libya. At the moment, he is living in a reception center near the Tunisian city of Djerba, a popular tourist destination.

Tunisia, it seems, doesn't want refugees any more than Libya does. Samuel A. claims that a Tunisian man helping the Red Cross yelled at him: “Get on a boat already so we can be rid of you!” Nevertheless, cities on the Libyan border are preparing for a new wave of migration due to the civil war in that country. Authorities have filled halls with wooden beds and are stockpiling medication in case tens of thousands of people flee Haftar's siege on Tripoli.

Samuel A. sits in a cafe outside the Tunisian camp. He pulls the sleeve of his sweater up his left arm, revealing a tattoo made up of fine, blue lines. Much of it is scarred over. “They tried to cut out my tattoo while I was still alive. I watched nine people die,” he said.

Samuel A. was “on the path to success,” he said. He was a talented university student, but he was politically persecuted. His fighting spirit has in the meantime been extinguished, his soul damaged. “I have seen,” he said, swallowing several times, “things for which I cannot find words.”

His last attempt to flee to Europe was more than one year ago, on Valentine's Day. The Libyan smugglers had told him the sea crossing to Italy would take four hours. After 14 hours, the coast guard arrested him and put him in a refugee camp in Tripoli. “We lived with 300 men on a concrete floor,” he said, adding that there was hardly any food and hardly any light. He also described how some of his fellow prisoners were tortured: “With their hands and feet tied behind them, sticks to the soles of their feet, with leather whips — all of it.” He then showed some videos.

One day, the employee of an aid organization came by. Samuel A. was called in to translate her conversation with the camp's Libyan director. Samuel A. complained to her about conditions in the camp and about his uncertain future. When the woman left, the director summoned him again. “They beat me to a pulp,” he said. He spent three months in a cell in solitary confinement with no daylight. The next time the aid workers came to visit, Samuel A. just smiled and said he was fine.

Source: SPIEGEL