In the early hours of a Sunday in late November, 16-year-old Jeancy Kimbenga tried to reach Europe for a third time. He was on one of three dinghies that landed on the Greek island of Lesbos that day from Turkey.

In the early hours of a Sunday in late November, 16-year-old Jeancy Kimbenga tried to reach Europe for a third time. He was on one of three dinghies that landed on the Greek island of Lesbos that day from Turkey.

On that occasion, as with his two previous attempts, Jeancy claims he was forcibly returned to Turkish waters.

So-called pushbacks, without consideration of a migrant's individual circumstances and without any possibility of applying for asylum, are illegal under international human rights law.

Greece has denied it uses such methods, insisting it is complying with European and international law and protecting the borders of the European Union.

During this third attempt to get to the EU, Jeancy, who is originally from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, documented part of his journey in the hope that the evidence of him being on Greek soil would prevent him being sent back to Turkey.

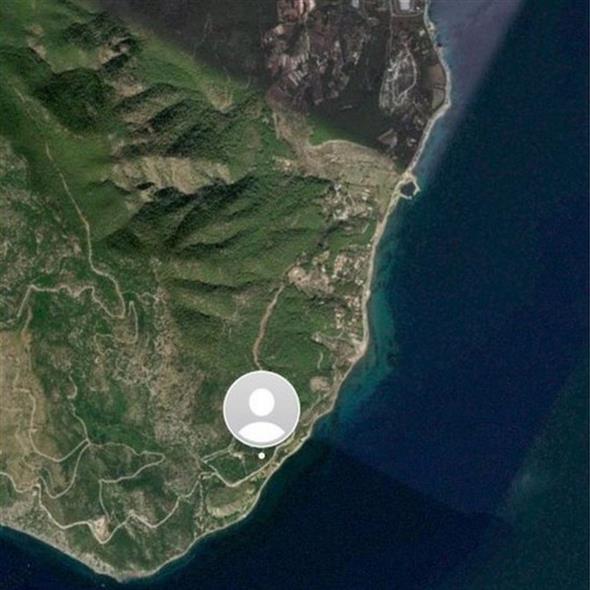

It was still dark when the three boats landed on the southeast tip of Lesbos, known as Kratigos, on 29 November.

The new arrivals gathered in a forest nearby and waited for dawn, sending photos and their GPS location to Aegean Boat Report, a Norwegian NGO that monitors migrant flows in the area.

Hours later, local academic Kostas Theodorou was cycling with his wife in the area when they ran into two women who claimed they were migrants who had just arrived on the island a few hours earlier.

The women said they were both Christians, pregnant and had not eaten for three days.

“They said they wanted to go to hospital or the migrant camp. My wife left to get some cash so that we can put them in a taxi,” said Mr Theodorou, an assistant professor at the University of the Aegean. But when he suggested calling the police, the women feared their passage to Europe would come to an abrupt end.

The migrant groups then left the forest and headed north, taking further photos of the places they passed. Aegean Boat Report published their whereabouts on Facebook and contacted Greek authorities.

The BBC has independently verified the migrants' material and several locations where they were walking in south Lesbos.

Jeancy Kimbenga and the others were met by a team of Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG) officers and put on a bus. They were told they would be taken to a special camp for quarantine because of the Covid-19 pandemic. At least two coast guard number plates and one officer are visible in the footage the BBC has acquired from the scene.

Jeancy says what followed deeply traumatised him. The bus drove for a couple of hours to the north of the island and stopped at a small port where men in balaclavas were waiting. The teenager recorded a video on his mobile inside the bus.

“They dressed up like ninja[s], they want to make us get on a boat and send us back to Turkey,” he is heard saying.

The boy alleges that the Greek officers then took everyone's phone, beat them heavily and forced them on “a big coast guard boat with something like a cannon in the front side” that took them out to sea.

There they were forced into life rafts and were left to drift towards Turkish territorial waters, he said. It is not clear why, but only two of the three groups that arrived in Lesbos that Sunday morning were sent back.

Hours later, at 02:40 on 30 November, the Turkish Coast Guard picked up 13 migrants from a life raft, off Cape Kadirga to the north of Lesbos.

The woman in the red sweater, who met Kostas Theodorou and his wife, can be seen getting off the boat, in a photo released by the Turkish coast guard. Jeancy says he too was on that boat.

Less than three hours later, a second raft with 18 migrants was rescued in the same area. A man with a fluorescent print on his sweater, who was pictured in the forest in Lesbos the previous morning, is seen leaving the Turkish Coast Guard boat.

Dozens of similar incidents have been reported in recent months and NGO Aegean Boat Report alleges that since the start of the year Greek authorities have carried out close to 300 pushbacks. Turkey accuses its neighbour of adopting the practice too.

Is Greece still a gateway to Europe?

How the migrant crisis changed Europe

Turkey moves to stop Greece pushing migrants back

Turkey says millions of migrants may head to EU

Greece, however, insists it “does not participate in so called pushbacks”, and Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has condemned the allegations as “an insult to the Hellenic Coast Guard”. Instead the country blames Turkey.

Migration and Asylum Minister Notis Mitarachi told the BBC it was Turkey's responsibility to eliminate smuggling routes and “protect human life at sea by preventing unseaworthy boats to leave Turkish soil”.

Turkey signed a deal with the EU in 2016 to stop migrants and refugees crossing into Greece, but said this year it could no longer enforce it.

It is not just Greece in the eye of the storm but also the EU's Border Agency, Frontex, which assists Greece in guarding the bloc's maritime borders.

It has now been accused of helping, or turning a blind eye to, pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, and the latest allegations have sparked one of the biggest crises since its creation.

Only last month, at a Frontex meeting on pushbacks, the Swedish representative presented evidence of Swedish officers witnessing one off the island of Chios.

An internal Frontex report, seen by the BBC, describes several Serious Incident Reports (SIR), listing suspected irregularities or rights violations. One of the most detailed accounts – labelled SIR 11095/2020 – tells of an incident that took place in the night of 18-19 April 2020; it says a Frontex plane witnessed a pushback, and that Greek authorities urged Frontex to fly elsewhere.

Source: BBC